We are now full swing into the summer blockbuster season for Hollywood, and let’s take a tally of movies that are currently out or soon to arrive that originate from the pages of comic books. Captain America: The Winter Soldier. The Amazing Spider-Man 2. X-Men: Days of Future Past. Hercules. Guardians of the Galaxy. Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Sin City: A Dame to Kill For. Kingsman: The Secret Service. Big Hero 6.

All of this, without mentioning the big hitters coming soon, such as the second Avengers movie, or the one that finally brings Wonder Woman to the screen while pitting Batman v. Superman. All of this, a range of titles for the young to the mature. And these are only Hollywood films. Consider all of the movies made from comic books around the world, and the numbers are staggering. The top ten comic book adaptation movies have grossed around $4.05 billion dollars in just over a decade, proving their dominance at the box office in the United States and around the world.

And we cannot forget their current and upcoming presence in television. From Arrow and Agents of SHIELD to the upcoming Flash and Constantine, comic books continue to make the transition to live action while also being adapted into animation.

There is no doubt; comic book adaptations are big business.

But, could the sudden success of comic book adaptations, as driven by the superhero genre, be one of the problems that fractures the fandom for these characters and this medium in general?

A while back, in 2006, I wrote a paper, and presented it at a Comic Arts Conference at Comic Con in 2007, that considered the problems and possibilities of adapting comics from the page to the screen. I was chiefly focused on the issue of how readers’ interpret and engage with this sequential art form. I argued that when adapting a comic book to film, the producer need to be concerned with fidelity to both the sensory and the narrative levels of the comic book, since these are both levels with which the reader engages in order to make sense of the comic book. A reader will come to develop certain expectations for what will be seen in the film based on these two levels. From this conclusion, I argue that producers need to be respectful of the fans of the comic book they are adapting, and that they can be respectful by being aware of the need to at least address the faithfulness of each level.

Which, of course, does not at all mean that they do that. On the sensory level, there may be changes needed to costumes, sound effects, the appearance of the people playing the characters. On the narrative level, depending on the comic book being adapted, producers may be able to hew very close to the story, or they may need to make adjustments for the thousands and thousands of pages that tell the characters’ stories.

All of this set-up is to say that the increased amount of comic book adaptations, into film and television, could becomes the means by which a fandom is fractured.

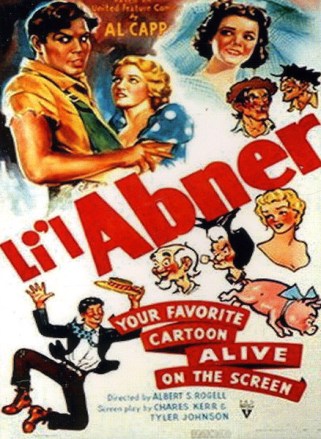

Back in April, when I attended the Popular Culture Association conference in Chicago, there was a presentation from DePaul University’s Blair Davis, who is a specialist in adaptations. His presentation focused on not on the modern trend of adapting comic books, but on the adaptation of newspaper comic strips from the 1930s into films. I had never heard of either the strips or the movies he was discussing, but his discussion of them indicated that they had undergone similar issues that we see in today’s comic book adaptations.

According to Davis, at the time when the marketing for these adaptations was coming out, there was agony by fans of the comic strip that the comic strip character would be “movified” — that, in some way, the movie version would lose something of the nature of the character with which they had fallen in love. This concern echoes modern sentiments; one can look at the current vitriol over the casting of Michael B. Jordan as Johnny Storm or Gal Gadot as Wonder Woman to see how fans react when one of their favorite characters is being adapted in a way that the fans feel is disrespectful of or unfaithful towards the character. Davis saw these marketing ads as trying to moderate these negative responses, presenting the idea of meeting this character “in person” via the film and talking about the character as if it is now “real-life” even though it is still fictional.

I found these marketing campaigns fascinating. They appear to be positioning the film as superior to comic medium because film allows for the characters to “come to life” and break free of the restraints of comics. The ability to add motion, sound, real people, all provides for a greater depth and dimensionality to it. However, by positioning these films as superior, and comics as inferior, for this lacking on the sensory level, then the argument could be extended to the comic fandom subculture. In a sense, these campaigns could be seen as positioning this fandom as inferior given the medium, seeing the medium’s fans as inferior to fans of film medium. Of course, this would be odd, given how film fans were seen as “lower class” at the time, but such positioning could be an attempt to position film as better than those “even lower class” comic fans, especially if those fans are adults.

Davis’ in-depth analysis was to consider how the marketing campaigns were rhetorically “destroying” the comic medium. For example, a poster would show the character emerging from a comic panel, bursting the lines of the panel as if to show that it no longer needs the space and the restriction that comes with it. To me, this rhetoric further positions the medium as inferior, by demonstrating that the adaptation is leaving it behind to become something superior. Such a marketing campaign would show an adaptation strategy that only wants to refer to the original source, but perhaps does not want to respect it and the fans of it?

All of this got me to think about how much the phenomenon of fractured fandom may be due to the proliferation of adaptations.

Think back to those 1930s. Think back to all of the Batman or Superman or Spider-Man adaptations over the past six decades. You have the original source, the canon, on which the adaptation is based. There are fans of that canon; there would have to be, usually, to generate enough interest in creating the adaptation. However, once the adaptation comes out, they may no longer be alone. In seeing the adaptation, new fans could be incoming, and some may even go back to engage with the canon. However, not all fans will go on to become fans of the canon. They may remain only fans of the adaptation.

Given that an adaptation may not be faithful replications on either sensory or narrative levels, what these news fans may be preferring could be very different from the original source. Thus, their preferences could be very different from those of the original fans. And with each new adaptation, a new fandom can emerge, further creating different factions of fans who prefer different versions of the canon. Over time, the development of such factions would most likely produce the hierarchy of superiority, where fans position themselves in relation to one another based on not only their preferences, but their “primariness.” That is, they may claim that being fans of the original source before the adaptation makes them the superior fan, the ones who were there before the material became “popular” or “mainstream.” The “real fan” could be positioned as the fan of the canon, and not the adaptations that could be seen as diluting the canon.

The more versions of the canon, the higher possibility that different people will find something they like, and the larger the audience becomes, and the more there are factions within that audience who will disagree over the legitimacy of the canon.

Factions due to preferences could also result in arguments over the reception of adaptations. Different interpretations of what is legitimate could cause debates — and depending on which source of material from which they are drawing their argument, each side could be right. Once an adaptation is produced and distributed, once it earns the money seen in the past decade, the adaptation becomes as legitimate, if not moreso, than the original material. Given this legitimation, the factions could be entrenched in their debates

Through comic book adaptations, you can end up with fans of different versions of the Joker arguing over which is the best one. You can have people who love the Oliver Queen in Arrow but do not like him in his original comic book title. You can have people complaining about a fine young African-American actor playing a role many see as only meant for a white actor.

And this phenomenon would not be limited to comic book adaptations. Any adaptations could produce similar fractured fandoms. You can have the fans of the original Doctor Who looking down on those Whovians who are only fans of the reboot. You can have people upset over the J.J. Abrams version of Star Trek. You can have people arguing over changes in scenes from book to screen, such as with Game of Thrones.

Which faction is correct? Does one have to be over the others? I would not argue for an answer to either. But we should recognize the fracturing occurring, and the extent to which the Hollywood model of adaptations adds to this process. Hopefully, at some point, all factions will recognize each other as legitimate — that no matter which avenue you take to get into the fandom (canon, adaptation, reboot, etc), the main thing is to be a part of the fandom, expressing your affection along with everyone else.